The Future of Chestnut Prices

Our first post focused on the supply of chestnuts and offered some reasonable projections as to chestnut supply. In it, we reached three important conclusions:

The chestnut industry is 50 - 100+ years behind other similar commodities. It is an infant in the tree nut industry.

It currently is producing roughly 10 Million pounds per year, and

Industry supply is likely to grow substantially over the next 35 years. If we use the pistachio industry as proxy, the US would see a 23-fold increase in chestnut production over the next 35 years.

That’s great news for those of us in this industry. But, economics would tell us there is a likely tradeoff between such a large increase in supply and the price per lbs. that growers would see in the market. That tradeoff is the central question for this second post.

The Data

First, I want to reiterate where this data comes from. The good people at the Economic Research Service at USDA have been collecting data on various tree nut crops (and many others) for quite some time. This particular dataset goes back to 1981 and ends in 2024. You can access it here (just scroll down to “Tree Nuts” and click on “Download CSV”). The .csv file contains a range of data on Almonds, Hazelnuts, Pecans, Pistachios, and Walnuts. The main variable of interest today is “Price received by growers”. I should note too that these are the prices received in August of each year.

Do prices fall?

Here again, we do not have great data on chestnuts. But, we can look at the price histories of those other nuts: almonds, pistachios, hazelnuts, and more. If we see prices falling sharply with supply, then demand does not increase as quickly as supply does. Conversely, if market prices actually increase with supply, then demand is rising faster than market supply.

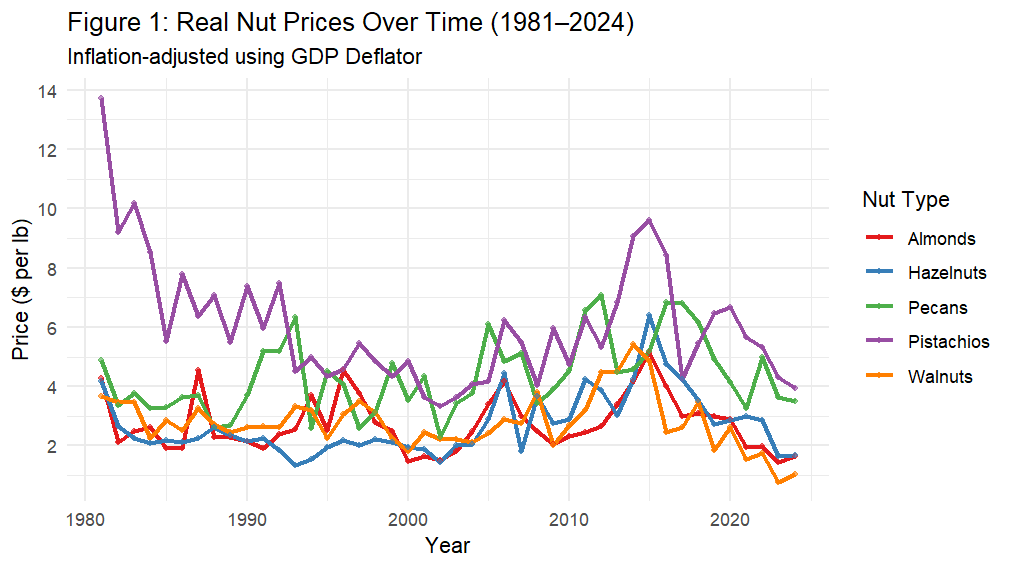

Figure 1 illustrates “Real” nut prices over time. This means that I’ve already adjusted these prices for inflation and converted them all to 2024 dollars. From 1980 through 2015, the real price per lbs. for most of these nuts actually increased, with fairly dramatic growth happening between 2000 and 2015. Over the full-period though, the prices have all stayed largely between $2-$6 per lbs.

This is a stable pricing picture. There is absolutely variability, but the basic band of pricing remains quite stable over the long-term. The question then is how does that correspond to output? Figure 2 illustrates the growth in nut supply over this same time period.

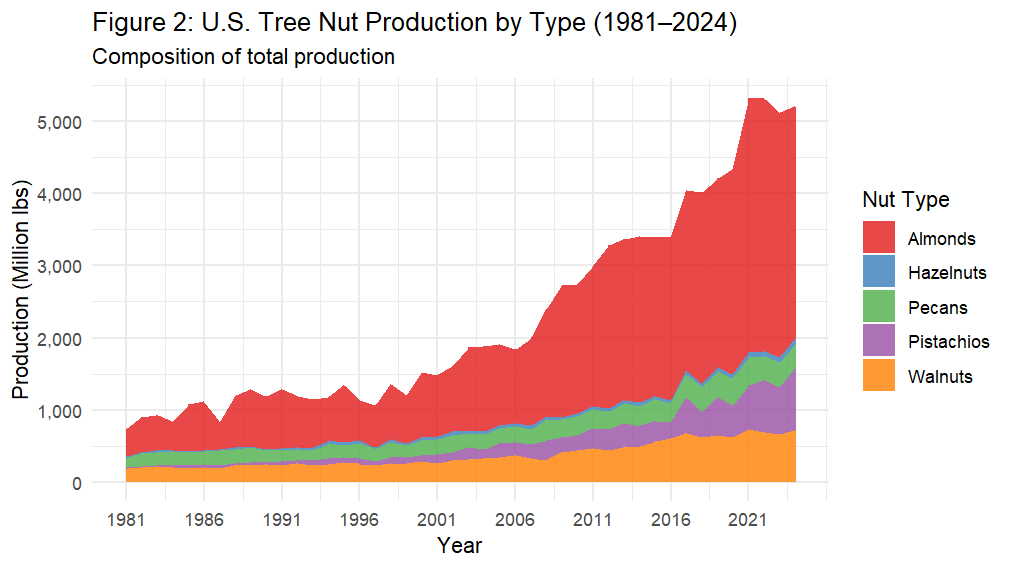

These output levels grow in really quite smooth and exponential patterns. For the majority of the nuts depicted here, output levels have more than doubled since 2006. Their prices though are only slightly smaller. This suggests that in this phase of development, the demand for these nuts is not sensitive to output.

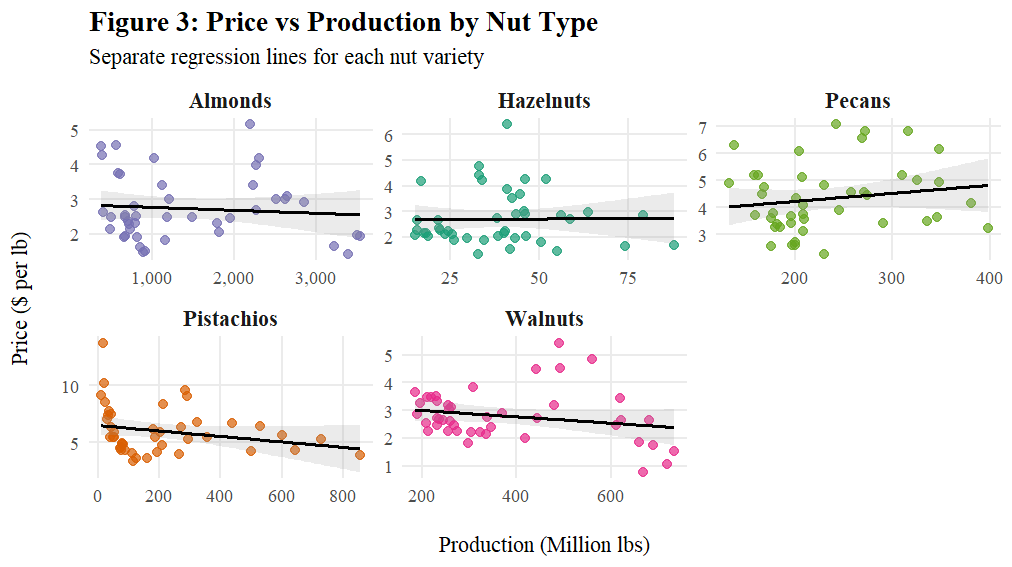

Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between prices and output levels for each of the tree nuts in this analysis. In economics terms, we call these kinds of markets price inelastic, which is just our way of saying, “producers bring more to the market, prices hardly change.” We might see some volatility in the short-term (e.g. Walnuts), but the medium- to long-term prices fall only slightly - with Pecans being the primary outlier. If Chestnuts follow suit (and there’s no reason to think they wouldn’t) as output levels grow the real price per lbs. should fall, but slightly.

Using some econometric tools, we can actually generate a reasonable forecast of the wholesale price of Chestnuts (in today’s dollars) as production expands. Using the historical data on all of these nuts, I’m able to estimate just how sensitive to prices this industry is as a whole. The answer, as I noted above, is not much. On average, a 1% increase in overall industry supply is correlated with a decrease in the real price per lbs. of about 0.33%. For example, if the industry supply was 5 Billion lbs last year at a price per lbs. of say $3.00, then an increase of 50 million lbs. should see prices fall from $3.00 to $2.99. That’s right, a penny.

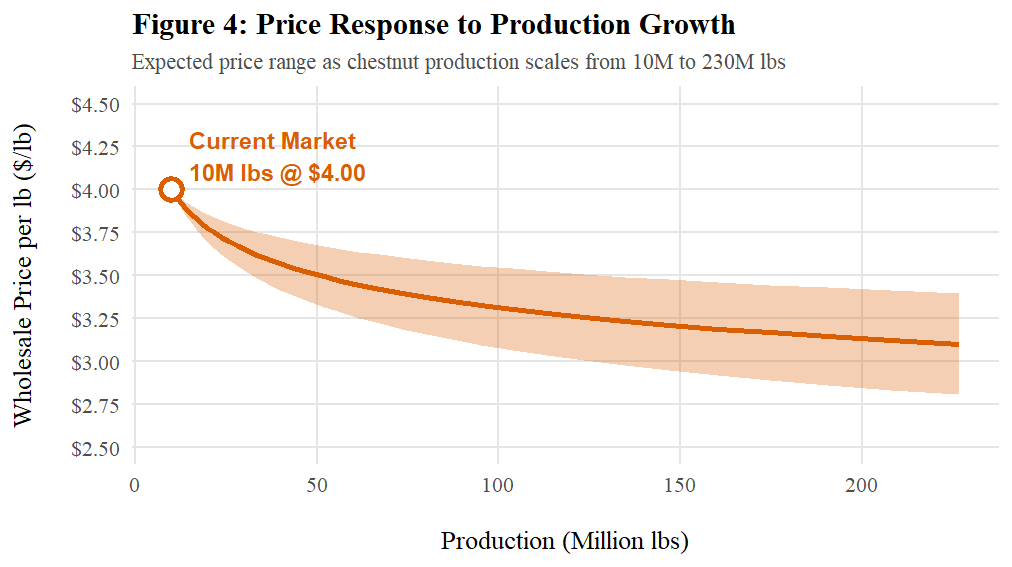

Figure 4 puts this all together for us. Based on our best guess for production (see our first post), we do expect the real price per lbs. to fall over the next 40 years but slowly. This assumes the Chestnut market operates just like the industry as a whole. There are likely several reasons it won’t (in the favor of growers) , which I think makes this forecast very conservative. But that’s a good thing.

All told, this forecast suggests that this $40 M industry today will reasonably generate more than $630 M in total revenue by 2060. That represents a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.2%, and again I think that’s a pretty conservative estimate.

The data paint one pretty clear picture: this industry is still taking off and it has a long way to go (over decades) before it matures. The immediate challenges now must turn toward cultivating new markets and creating more depth on current ones.

It’s going to be a fun ride. Get in!